For American fund managers and Indian start‑ups alike, using the chatbot could be tantamount to CC‑ing a rival on every brainstorming session.

When the Chinese start‑up DeepSeek released its R‑1 chatbot in January 2025, the launch felt like a Silicon Valley fairy‑tale told in Mandarin. Two months and fifty‑seven million downloads later, the numbers were jaw‑dropping. On Apple’s U.S. App Store, it eclipsed ChatGPT, in India, it jostled for the top spot in every major language category. Reporters praised its fluency and its price tag; free. What mattered less in that honeymoon week was how the software moved across the internet. On April 16, 2025, researchers working with the U.S. House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party released their report, DeepSeek Unmasked: Exposing the CCP’s Latest Tool for Spying, Stealing, and Subverting U.S. Export Control Restrictions, revealing that every user prompt, device fingerprint and behavioural tic is routed across the Pacific to servers run by China Mobile—a carrier the U.S. Department of Defense lists under Section 1260H as a Chinese Military Company.

The first rupture appeared on 29 January when cloud security firm Wiz stumbled upon an exposed ClickHouse database tagged “ds‑log‑prod‑001”. Anyone with a browser could have accessed more than a million log lines: raw chat history, API keys, and even internal service tokens. Wiz engineers demonstrated that with two clicks they could seize “full database control”, inject malicious code and pivot into the rest of DeepSeek’s infrastructure. A week later mobile forensics specialists at NowSecure published a parallel autopsy of the iOS build. Their findings read like a checklist of everything Apple’s security team tells developers not to do: hard‑coded encryption keys, deprecated 3DES ciphers and App Transport Security switched off globally, allowing chats to travel unencrypted. The company urged enterprises to ban the app outright. However, DeepSeek’s parentage turned out to be even more troubling.

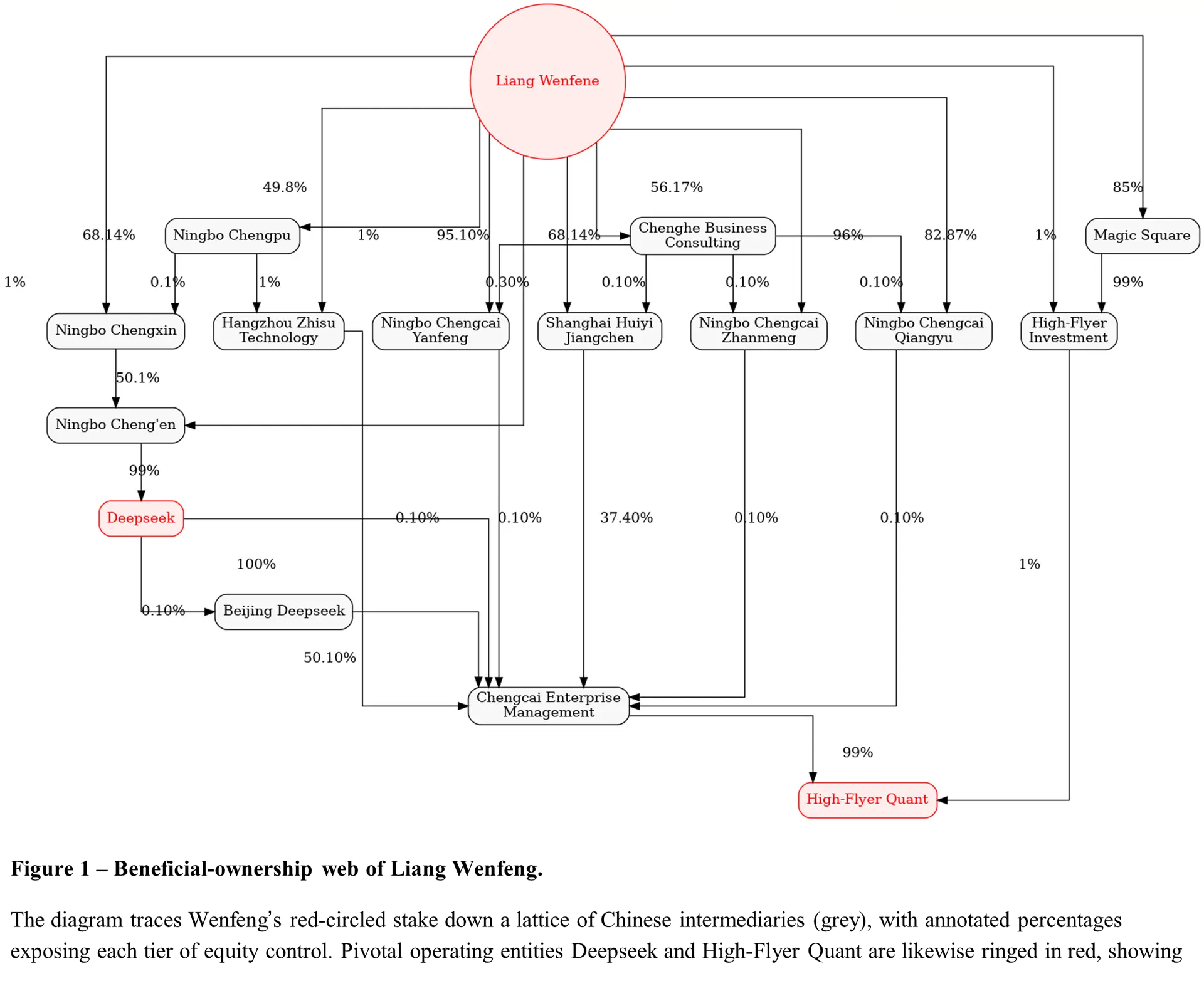

Corporate registries in Zhejiang and the Cayman Islands show the chatbot is a wholly owned offshoot of High‑Flyer Quant, a hedge fund founded in 2016 by the 38‑year‑old trader and CEO of Deepseek Liang Wenfeng. Reuters reporting confirms that High‑Flyer pivoted from equity markets to artificial

intelligence research in 2023, building two super-computing clusters stuffed with Nvidia A100 processors before U.S. export controls came into force. On Capitol Hill the discovery set alarm bells ringing. Washington had barred Beijing from buying the world’s most coveted AI chips, yet here was a Chinese firm running a model of near-GPT-4 heft on hardware Washington thought safely out of reach.

The House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) further codified those fears in their recent report, accuses the firm of “spying, stealing and subverting” by siphoning petabytes of conversational data and laundering it through a thicket of shell companies to evade export rules. Committee members John Moolenaar and Raja Krishnamoorthi want answers not only from DeepSeek but from Nvidia, whose chips, roughly 60,000 of them, according to Business Insider—ended up in Liang’s Hangzhou data centre via middlemen in Dubai and Singapore. Nvidia insists it obeys U.S. law, but lawmakers are now drafting “chip end‑user tracing” legislation to brand each accelerator with an immutable provenance tag.

While American regulators consider subpoenas, New Delhi has already moved. On 5 February, the Indian Ministry of Finance circulated an internal directive forbidding officials from using DeepSeek (and ChatGPT) on government devices, citing risks to the “confidentiality of government documents and data.” Sources say the Computer Emergency Response Team of India (CERT‑In) is preparing a broader advisory under the new Digital Personal Data Protection Act that could push local app stores to delist the software if it fails a security audit. Other democracies have gone further: Italy, Australia and Taiwan have banned DeepSeek from public‑sector systems, with Taipei warning of “systemic espionage risk”.

What exactly is at stake for countries such as the United States and India? Language‑model telemetry, say analysts, is qualitatively different from the browsing‑history bonanza that powered Cambridge Analytica. A generative AI does not merely record what users click, it ingests the content they originate, draft policy memos, legal arguments, unpublished code repositories, and intimate medical questions. Through a technique called model inversion, adversaries can reconstruct fragments of that training data. In practice, that means Beijing could fish out a U.S. senator’s embargoed speech or an Indian bureaucrat’s budget note and feed the text into targeted influence campaigns long before it ever reaches the public domain.

Beyond political manipulation lies industrial espionage. High‑Flyer Quant’s pitch decks boast of “harvesting alternative data at planetary scale”. If every trade idea whispered into DeepSeek ends up in a Hangzhou warehouse, the company enjoys a real‑time map of market sentiment unavailable to Wall Street—and unpoliced by the Securities and Exchange Commission. For American fund managers and Indian start‑ups alike, using the chatbot could be tantamount to CC‑ing a rival on every brainstorming session.

Defenders of open innovation counter that paranoia will balkanise the internet, that aggressive export controls slow scientific progress. Yet even optimists blanch at DeepSeek’s specific tactics. Wiz’s database trove confirms the app records keystroke timing, an input often used to build biometric “behavioural fingerprints”. Combine that with device IDs and IP addresses and you have a persistent, hard‑to‑spoof surveillance token attached to millions of users worldwide. In democracies, such dragnet profiling would trigger a cascade of court challenges; in China, recent amendments to the Counter‑Espionage Law oblige companies to hand that data to state agencies when requested.

From Beijing’s vantage, the collection is both legal and geopolitically priceless, a mine of linguistic gold that can improve home‑grown AI models while enriching agencies tasked with mapping public opinion in rival states. The People’s Liberation Army has published openly about using sentiment analysis to anticipate unrest; DeepSeek offers a sentiment feed written by citizens themselves, timestamped and context‑rich.

India’s vulnerability is especially acute because its flagship Digital Public Infrastructure, Aadhaar biometrics, the Unified Payments Interface, and the forthcoming Health Stack—bundles citizens’ identities into interoperable layers. If DeepSeek could cross‑reference Aadhaar‑seeded phone numbers with conversational data, it might assemble dossiers on millions of Indians at a granularity Western intelligence services could only envy. The Finance Ministry’s ban is thus less a bureaucratic precaution than a firewall protecting the world’s largest democracy from a silent, synthetic wiretap.

The fight has now shifted to export enforcement and standards‑setting. American lawmakers want the Commerce Department to classify conversational logs as “emerging surveillance technology” under the Wassenaar Arrangement, forcing any foreign LLM that touches U.S. data to host and process that data on U.S. soil. India is drafting secondary rules under its new data‑protection law to require onshore storage for “significant data fiduciaries”, a category DeepSeek would almost certainly enter. Liang Wenfeng, for his part, threatens to launch “sovereign clouds” region by region, claiming local data will stay local. Investigators note that such promises evaporate once the traffic tunnels through China Mobile’s backbone.

Whether legislators can keep pace with a company that spins up shell entities overnight is an open question. What seems certain is that DeepSeek has achieved something rare, it has united Republicans and Democrats, Indian bureaucrats and Silicon Valley privacy activists in the conviction that some conveniences are simply too costly. The cautionary tale is spreading, a tool offered free of charge, too powerful and too permissive to be real, turns out to be subsidised by the oldest currency in geopolitics, i.e. intelligence.

First published on https://www.news18.com/amp/opinion/opinion-packets-to-the-party-how-deepseek-funnels-data-to-beijing-ws-l-9306632.html