For Southeast Asia, the signal is clear, India is serious about its eastern maritime frontier, where China’s influence intersects with ASEAN’s strategic anxieties.

At first glance, the Great Nicobar “holistic development” plan looks like a familiar Indian story: build a port, lay an airport runway, power the grid, and grow a township. Look again at the map, and it reads less like a construction schedule and more like a hard-nosed geopolitical play.

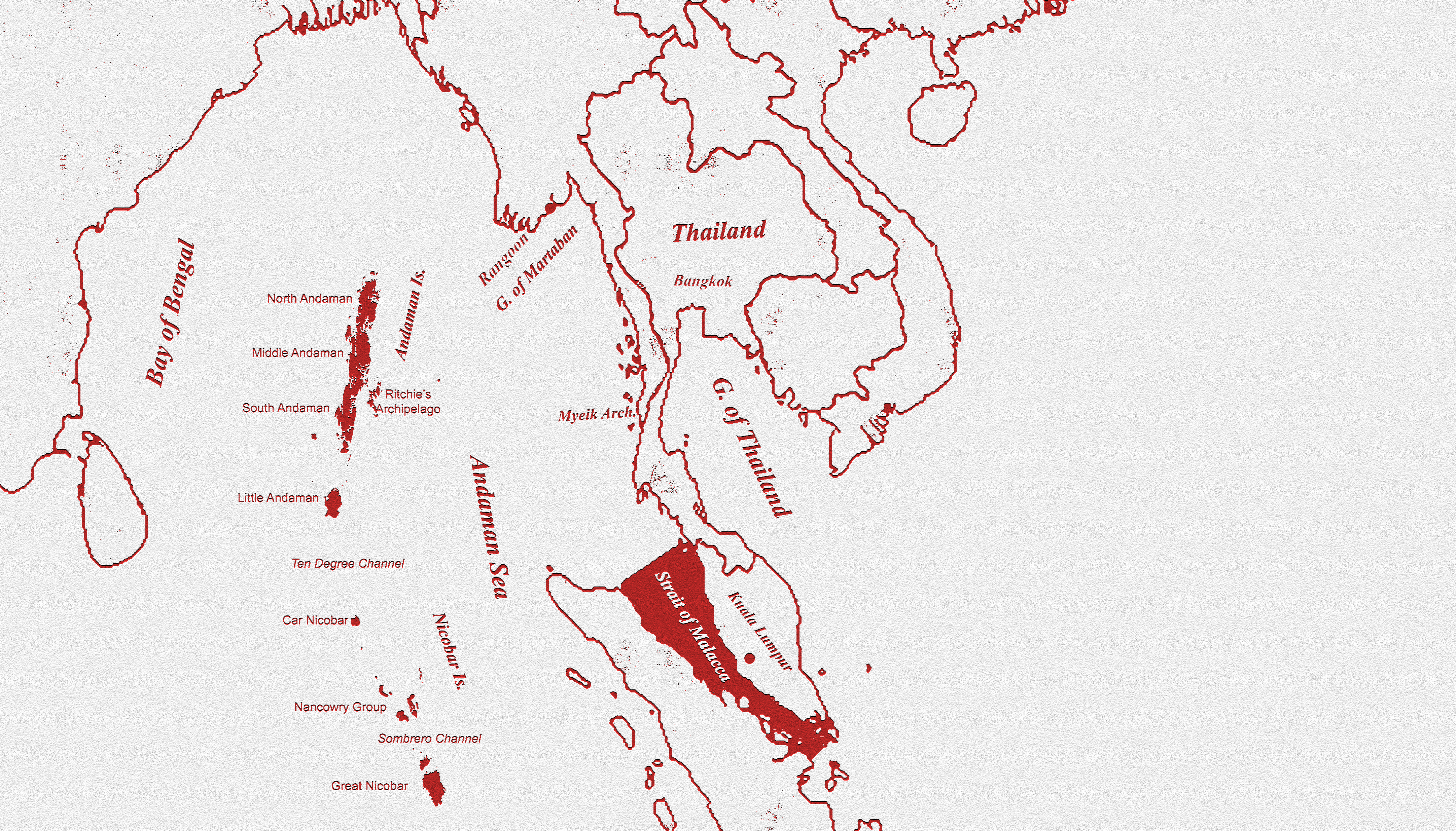

Great Nicobar sits on the Bay of Bengal’s southern edge, near the approaches to the Malacca Strait, the hinge between Indian Ocean and the Pacific. In the Government’s own bidding document for the Galathea Bay transshipment port, the geography is stated plainly. The island is about 40 nautical miles from the Malacca Strait international shipping channel, and about 35% of annual global sea trade moves through the Malacca corridor. For China, whose trade and energy lifelines run across the Indian Ocean and then through Southeast Asian chokepoints, this is the part of the map that matters in any crisis.

But leverage here is not the cartoon idea of “shutting Malacca.” The real strategic question is subtler. Can India raise China’s uncertainty and costs by watching, tracking and, if needed , contesting movement, without turning maritime competition into a war on commerce? The plan’s architecture is built for that answer. In formal environmental filings, Great Nicobar is framed as an integrated build: an International Container Transshipment Terminal (ICTT) planned at 14.2 million TEU, a greenfield international airport designed for 4,000 peak-hour passengers, a 450 MVA gas-and-solar power plant, and township and area development across 16,610 hectares, with a stated project cost of about ₹75,000 crore.

The port’s Phase-I bid document pegs Phase-I capital cost at around ₹18,000 crore, and lays out a ramp from roughly 4 million TEUs by 2028 toward 16 million TEUs in the ultimate build-out. Why does that matter for global supply chains? Because India still pays a strategic “tax” for not owning enough of its maritime switching nodes. A Government release notes that nearly 75% of India’s transshipment cargo is handled at ports outside India, and that Colombo, Singapore and Port Klang handle more than 85% of this traffic.

When Indian cargo must be relayed through foreign hubs, India loses time, fees, and predictability. In a disruption; conflict, sanctions spillover, a freight shock, dependence becomes vulnerability. Now place China in the backdrop. Beijing’s maritime strategy around India is best understood as a network: access, logistics and influence across the Indian Ocean, commercial port relationships, infrastructure finance, and periodic naval deployments.

India’s response is increasingly about denying China a free run in India’s near seas while ensuring India can operate at range. The Andaman and Nicobar chain is central to that response. A Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA) brief underlines that the Six Degree and Ten Degree Channels in the Andaman Sea leading to Malacca are vital sea lines of communication.

Great Nicobar strengthens that geometry by adding depth and endurance.

Maritime power is not only about sensors and ships. It is about sustainment; fuel, repair, berthing, aviation support, and the ability to surge repeatedly without retreating to the mainland. A port-airport-power complex makes persistent maritime domain awareness more feasible and faster response cycles more routine. The subnautical contest sharpens the case. Chinese submarines can enter the Indian Ocean, but geography constrains entry routes and imposes friction. Several analyst assessment note that Chinese submarines access the Indian Ocean through straits such as Malacca, Lombok, Sunda or Ombai-Wetar.

India does not need to promise interdiction; it needs to improve detection, cueing, and uncertainty. If the probability of being tracked rises, the cost of deploying quietly rises too, and China must allocate more assets and attention to simply move. For Southeast Asia, the signal is clear, India is serious about its eastern maritime frontier, where China’s influence intersects with ASEAN’s strategic anxieties. A functional node at Great Nicobar can underpin disaster relief, evacuation operations, anti-piracy responses, and maritime policing, public goods that translate into influence when delivered reliably.

But masterstrokes are judged by execution and legitimacy. The Government acknowledges the environmental scale: a July 2024 release notes Stage-1 approval for diversion of 130.75 sq km of forest land, estimates potential tree impacts below 9.64 lakh, and sets special conditions for biodiversity planning with institutions such as WII and ZSI. In February 2026, media reports said the National Green Tribunal upheld clearances while directing strict compliance with safeguards.

Call Great Nicobar a masterstroke, provided India builds a commercially competitive transshipment hub that shipping lines actually choose, and a security-enabled logistics ecosystem that strengthens supply chains without militarising commerce. If it succeeds, India converts geography into leverage by ensuring that, in any crisis, China must factor Indian visibility, Indian reach, and Indian options into every calculation.